- Home

- Alicia Drake

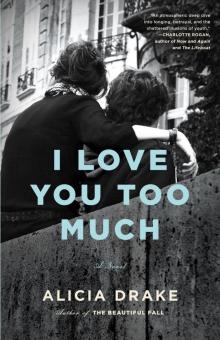

I Love You Too Much Page 6

I Love You Too Much Read online

Page 6

She took her sleeping pill and then she switched off the bedside light and stroked my head in the dark. She touched my hair. I held her hand against my cheek and smelled the inside of her wrist, felt the pulse of her on my lips. I was happy then.

Chapter Five

Maman was jogging down the hotel corridor; Cindy was running to keep up, pushing the pram with Lou, who was screaming and punching the air, writhing around on her sheepskin rug.

“Come on, Paul, I’m going to be late,” Maman called out.

Every time I touched a door handle or an elevator button in that hotel I got a massive electric shock. It must have been my sneakers. I had taken to slamming the doorknobs and buttons with my hand to lessen the shock of the charge. If I ran now, I’d give off sparks.

We pushed to get in the elevator. It was packed with people going to the thalasso, all trying to look cool about the fact they were in an elevator wearing white terry-cloth robes and white plastic slippers. There was no room for the pram.

“You’ll have to wait for the next,” Maman said to Cindy as the doors sucked shut.

I wonder if Cindy ever felt like shouting, ever felt like shoving her foot in the door and saying, Move your ass, I’m coming in. But she never does that; she just smiles, or if she doesn’t exactly smile, then she looks blank, she accepts. I’ve never seen her angry. Once I saw her upset when her grandmother died and she couldn’t go home to the funeral because she had no papers. Then she went quiet for days. But otherwise she is always smiling and nodding.

She reads the Bible every night and she has posters in her room that say things like GOD MAKES ALL THINGS BRIGHT AND BEAUTIFUL with pictures of daisies and sunsets. She’s got a poster of Jesus holding a child and saying, “Let the little children come to Me,” and His hair is gold and His beard is gold and He’s wearing a white gown like He’s just stepped off a cloud. My aunt Catherine has a painting of Jesus in her apartment, but her Jesus is wearing a crown of thorns shoved down on His scalp and He’s got blood dripping down His temples, and His face is battered and green.

People pushed to get out when the elevator doors opened, and then they ran across the foyer like it was the first day of the sales. There were two large rooms for breakfast, one with the food and the other with the tables. The waiter showed Maman straight to a table; she didn’t bother with the food. I went to check out the buffet. Scarlett was standing in the queue. She was right in front of me, so near I could touch her. She was putting chocolate chip cookies onto her plate, loading them on, three or four of them alongside slices of dark red salami. She turned and looked at me. Her eyes were yellow-green with a dark circle around each iris, like someone had drawn it on. I’d never been that close to her.

“Are you doing club ado, you?” she said.

“No,” I said. “Are you?”

“I’m not doing that shit. I’m fourteen.”

I wondered if she recognized me from school.

“Who are you here with?” she asked.

“My mother.”

“Which one is she?”

“She’s over there, in black, by the window.”

She looked across to where Maman was sitting. She checked her out. Then she turned back to me.

“She’s beautiful,” she said. “And she knows it.”

I waited for her to say something else, the sort of thing people usually say, like Why is she so thin and you’re so fat? or You don’t look anything like her, why is that? But she didn’t say that. She tossed back her hair and looked around at the tables of terry-cloth people.

“Fucking thalasso,” she said. “People paying money to get their cellulite hosed down with a cold power jet, what a joke. Remind me not to grow old.”

She wore strands of colored embroidery on her right wrist and a little black ribbon with a silver heart on it. Her arms were tanned and thin and she had scraps of dark purple polish on her fingernails. Her eyebrows were thick and black and arched like a woman’s, but beneath them she had the face of a girl.

She popped a gherkin in her mouth.

“See you later,” she said. She went and sat at the table where her parents were reading the newspaper.

“So what are you going to do today?” Maman asked as I sat down. She looked at my plate, counted the number of chouquettes there, but she didn’t say anything. “Are you sure you don’t want to do club ado?”

“I told you I’m not doing that.”

“What are you going to do all day? I’m putting Lou in baby club. Cindy, you need to come with me now to drop Lou off, then you need to pick her up at five o’clock because I don’t finish until five thirty. Have you understood that, Cindy?”

“Yes, madame, I’ve understood.” Cindy was feeding Lou a bottle. Maman got out a plastic folder with a cream card inside it.

“What is that?” I asked.

“It’s my schedule,” she said. “They’ve put me down for aqua gym straight after balneotherapy. I’ll never get there. Why do they make it so stressful?”

People started to get up from the tables, pushing back their chairs, checking their phones, standing up and draining their coffee, telling their kids to hurry, to leave the hot chocolate, there wasn’t time. It was just like Megève or the hotel in St. Barth where we used to go: guys on their phones, women trying to get to their spa treatments, rushing out of the room to dump their children at kids’ club. Piou Piou, Club Fun, club ado; the names are different, but it’s all the same—you pay your money and they take your kids away.

“So what are you gonna do, Paul?” Maman said again. She stood up and smoothed her black Lycra leggings against her thighs. I saw the waiter go by and check out her ass.

I shrugged. “Hang out.”

“Are you sure?” She looked at her watch and then she pulled out fifty euros from her bag and passed it to me. “I won’t be back until five thirty. I guess Gabriel can look after you when he gets here.”

I rolled my eyes.

“He can’t even look after himself,” I said.

But she wasn’t listening. She was giving Cindy instructions about feedings, talking about milk milliliters and droplets of medicine and Lou stuff. Everyone was trying to get out of the dining room at the same time—man, you could feel the tension—flapping their schedules, sneakers grating on the carpet, all the Lycra and terry cloth and plastic slippers generating kilowatts of electrical charge. Then Maman was gone, and Cindy was jogging after her with the pram.

I did a last tour of the buffet table. I picked up a pain au chocolat, a maple-syrup twist, and another handful of chouquettes. They are puffballs of choux pastry rolled in crystallized white sugar. I lick the pearls of sugar off first, then, when the choux pastry is wet and shiny, I pop it in my mouth and hold it there until the puffball collapses and turns to pulp.

I walked through to the bar and sat down on one of the big purple sofas. The coffee table in front of me had legs carved to look like huge lion paws with black claws sticking out. I watched the receptionists through a glass wall. Gwénaëlle was there, the receptionist who had checked us in. She was sitting on a stool, chatting to her colleague. She had taken off her shoes and I could see her beige stockings; I watched as she rubbed one foot up against her slim calf, like a cat.

Serge from the night before came into the bar with a slimmer version of himself. They sat opposite me and drank espressos and talked about how much they’d lost at the casino the night before. I played FIFA.

I looked up just as Scarlett walked through the hotel door. She was carrying a plastic shopping bag from 8 à Huit.

“What a hole,” she said as she sat down beside me on the sofa. She was wearing white frayed jean shorts even though it was cold out and she’d left the button undone so they were open on her tanned stomach. I looked down and I could see the top of her yellow panties. Serge looked up and stared at her.

“I just walked into town. There is nothing there, just a bunch of bourgeois women buying roast chicken.”

I la

ughed, but I didn’t say anything. I couldn’t think of what to say. She got her phone out.

“What the fuck is that about?” She pointed at a black shiny sculpture of a huge woman in a tiny bikini with her legs in the air. “That is sick,” she said. She took a photo of the sculpture. She didn’t seem to need me to say anything. She looked around; she checked out Serge. She took a photo of me and her on her phone and sent it to someone. That person must have sent something back because she started laughing. She was like that for a long time, texting and messaging, giggling to herself, while I sat beside her on the warm velvet sofa, gaming. It was a nice feeling.

“Where are your parents?” I asked after a bit.

“Golf and thalassotherapy.” She shrugged. “As usual.” And then she said, “Let’s go down to the beach.”

We walked past the outdoor pool where kids were having swimming lessons. There was lounge music being piped out of the bamboo. We went out to the promenade, where there were still some stragglers heading off to the thalasso. They looked odd walking along the road dressed in white robes.

“It’s like a psychiatric ward,” Scarlett said.

“Have you been?”

“Have I been where?” she asked.

“To the thalasso.”

“Yeah, I’ve been. My mom spends half her life in there. Here and in Quiberon. Quiberon’s not so bad because it’s got a hot tub outside. That’s cool.”

We walked past the glass dome of the thalasso; people were heading in there like bees to a hive.

“What do they do all day?” I asked.

“Nothing. That’s the point. They scrub you down with salt, they smother you with green algae that smells rank, and then they wrap you up in this plastic sheet and plug it in so you deep-fat-fry and sweat into the plastic. Then they get you out and hose you down with cold water and you have a bath with all these purple twinkly lights and they tell you all this crap about the benefits of seawater and how you are going to live for twenty-four thousand years. Then you spend hours lying around in there.” She pointed to the side of the building. “It’s got special glass so they can see us, but we can’t see them.”

“What do they do in there?”

“Nothing. My mom’s probably in there right now.” She stuck out her tongue at the glass building. “Yeah, that is the worst in there, you just lie around ‘resting’ and everyone reads Gala magazine and stares at each other to see who’s had bad plastic surgery. Then at the end of the week, they weigh you and tell you how much less stressed you feel. The joke of it is my mom never loses more than half a kilo, max.”

“How do you know all that?”

“I’ve been so many times and I watch people. Like you do,” she said, and she looked straight at me.

“My mom’s doing the ‘young mother’ treatment,” I said.

“Yeah, well, my mom can’t do that, can she? She’s not young and she hasn’t got a baby. She’s doing the anti-stress treatment. She’s got loads of that. Don’t I know it?”

I wondered if Maman still counted as a young mother. She would be forty next year. I guess she did have a baby.

We walked down the steps onto the sand. The beach was flat and it went on forever. The sun had come out after yesterday’s rain and there were runners out in shorts and kids from the hotel kids’ club being made to do a high-jump competition. There were masses of tiny white shells all over the sand. They crunched under our shoes as we walked. The sea was far out. It was odd; it wasn’t like a normal beach. There were no waves; there was no sound of the sea, no excitement, just these flat lines. It felt like a runway to somewhere.

We sat down together about halfway between the promenade and the sea. I dragged my fingers around like I was a digger, making little piles of the cold, clammy sand. Seven piles on each side of my body, small and round, each the same size.

“Where’s your dad?” Scarlett said.

“At work, I guess. They’re not together.”

“And the baby?”

“She’s not my dad’s.”

“What’s she called?”

“Lou,” I said.

“It must be nice to have a baby sister.” Her voice was different when she said that. Not hard and diamond-cut, but tender.

“She’s only my half sister,” I said. “She doesn’t actually do anything.”

“She will when she’s older. She’ll want to play with you then. She’ll hold your hand, she’ll look up to you. You’ll be her big brother.” She pulled a half bottle of vodka from her shopping bag.

“What about you? Have you got brothers and sisters?” I asked.

“An older brother.” She took a swig of vodka and offered me the bottle. I took a swig. I’d never drunk vodka before. I would have preferred Coke. “But he’s a total geek,” she said, “a mathmo. He’s doing his prépas.” She looked across at me to see if I understood the significance of what she was saying. Prépas meant he was doing a course to try to get into one of the grandes écoles, which are the best universities in France. It meant he was clever. It takes two years to do it, you work like crazy and then at the end you take an exam that is a competition, and only the top scorers get accepted for a grande école.

“My dad did that,” I said, “and my uncle too.” That is what my cousin Augustin would do after his bac next year. That is what my dad used to dream I would do.

“We used to hang out when we were little,” she said. “But then he got all serious when he went to high school. He became a Scout, you know, carrying the flag with the cross and singing Jesus songs. All he wanted to do was run around in his Scout uniform and study. Nothing else. He didn’t need me anymore.”

I saw her looking at me out of the corner of her eye, to see my reaction, I guess. I kept making my mounds of sand. She told me the name of the school where he was doing his prépas. It was the big Catholic school near us where the girl with black hair who lives opposite us goes. I’d had swimming lessons there when I was little. All the boys have to wear shirts with collars and have their hair cut above their ears, and the girls aren’t allowed to wear short skirts or makeup. Everyone says it’s so strict you get detention if you drop your ruler.

“I used to go to that school,” Scarlett said.

I laughed out loud.

“What are you laughing at?” she said.

I stopped laughing.

“What, you think I’m not clever enough to go there, is that it?” She made her eyes go narrow.

“No, it’s not that. I can’t imagine you there, that’s all.”

“Yeah, well, I got chucked out,” she said.

“What for?”

“Bad attitude.” She took a swig of vodka. “Big bad attitude, that is what they said. I’d been there since I was five. I just couldn’t take it anymore. Everywhere was dark and everyone was strict and uptight, telling me there was something wrong with me, that I lacked discipline. And all the kids looked at me like they were scared of me. The priests and the teachers there, they all go on about Christ’s suffering. They don’t know what suffering is.” Her mouth was tight when she said that.

She took her jean jacket off and I could see her breasts, pushed up and out for all to see. She kept jutting them out, as if they would reach the ocean. She was wearing a lip gloss that glistened pink and after she took off her jacket, I could smell the sweetness of her perfume. The boys at school talked about her breasts all the time; it was strange to think I was sitting here next to them. I wondered if she would let me touch them if I reached out my hand. I wondered what Guillaume and Pierre would say if they knew I was here, sitting next to Scarlett Lacasse on the beach in La Baule.

She got up then and threw the bottle to the ground.

“Chase me!” she shouted.

She ran all the way down the beach and I chased after her; she ran and ran and I ran after her down to the sea. She kicked off her black ballerina flats and they flew through the air, then she ripped off her shorts and I could see all of her lacy yellow

panties, and she went and paddled in the still sea. I took my shoes and socks off, but not my jeans. I rolled them up to my knees. I followed her into the sea. The water was freezing cold and green and it made my toes look yellow. Scarlett waded out really far, but still the water was only up to her thighs.

She went on and on, moving farther away from me. I stayed at the edge with just my feet and ankles submerged. Little silver fish darted across my toes. She looked like she was in a film, wading all alone in the sea with the wintry sun on her hair. Her head was down, like she was searching for something in the water. I watched her because I couldn’t take my eyes off her. I didn’t want to let Scarlett out of my sight, out of my life, now that she was here.

Chapter Six

After a while she came wading back to where I was waiting.

“I hate it when there are no waves.” She was like a little girl when she said that. She put her shorts back on and picked up her ballerina flats.

“Have you got any money?” she said.

“I’ve got fifty euros.”

“What are you waiting for?”

We walked back up the beach, past some old guys digging in the sand for razor clams. They had narrow forks and buckets and I heard one of them shout: “I’ve got him now, Claude.” We found a café tucked under the wall on the beach, just below the promenade. It was called Club de l’Étoile. It was warm inside; the floor was orange and the chairs were yellow plastic and there was some kind of Cuban music playing and little colored lights strung up above the bar. I loved that place. There was sand between the floorboards and starfish everywhere, dried starfish and little blue fake starfish on the tables and starfish shapes cut out of the wooden bar. The lady brought us cheeseburgers and fries with ketchup. We drank Coke. Scarlett told me her mom would be angry with her forever for getting chucked out of school.

I Love You Too Much

I Love You Too Much