- Home

- Alicia Drake

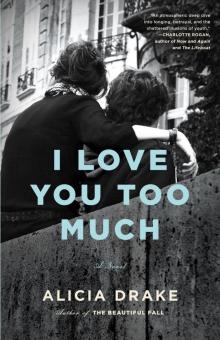

I Love You Too Much

I Love You Too Much Read online

Copyright © 2018 by Alicia Drake

Cover design by Lucy Kim

Cover photograph © Paul Bourdice / Millennium Images

Cover © 2018 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

First Edition: January 2018

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-55319-3

E3-20171205-NF-DA

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Untitled

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Alicia Drake

Newsletters

Prologue

Everyone thinks they know Paris: the Eiffel Tower and the old man playing an accordion in the street, couples kissing in cafés and horse chestnut blossom on fire in the green trees.

They don’t know about the secret code to get into your apartment building. They don’t know about waiting for the elevator to come, watching the thick black cable churn up the elevator shaft. They’ve never been to a children’s party here; never felt the party entertainer grab their wrist and say between his teeth: “That is enough.” Ça suffit.

There are no dirty shoes in the 6ème arrondissement, where I live. There is nowhere to get dirty. There are only pavements and the Jardin du Luxembourg. There is grass in the jardin, but you are not allowed to walk on it. And when there is snow they close the jardin, and when there is wind they put up a sign that says DANGER: RISK OF VIOLENT WINDS, BEWARE OF FALLING BRANCHES.

My Paris is the one same street between school and home. It is gray apartment buildings and heavy wooden doors that you step through into dark courtyards, still and damp where the ivy grows. My Paris is the sound of the concierge’s vacuum banging up against the front door and water pipes flushing baths away above my head. It is empty corridors of polished parquet four floors up and my feet not touching the ground. I hear the neighbors shout when Paris Saint-Germain scores. I hear the surge of the rubbish truck at night in the street below. It is many lives lived alone.

I was a child once in Paris.

Chapter One

It was September, the sky was big and blue, and Paris felt new again. I stood alone with my back against the wall. Warm drafts of stale air puffed at my legs from the vents in the concrete. There were gray circles on the floor all around my feet, chewing gum spat out and left for dead.

The other kids were pushing to get to the metal barriers that stopped us from spilling out into the road; girls and boys kissing hard, lighting up, texting, swearing at each other. They gathered like flies on a wall. There were girls screaming in tight jeans; they had breasts that showed and mouths that promised. The boys sat astride their mopeds and checked their phones; they reached down to pluck up the shiny club flyers that lay in a pool on the pavement. No one wanted to go home. No one wanted to be alone.

I looked up and saw him waiting. He was chatting on his phone, laughing behind his gold aviator sunglasses. He had a beard to match his brown leather jacket. He had let the beard grow when we were in Saint-Tropez that summer. He was sitting in my mother’s car with the music pumping so loud that I could hear it from where I stood.

He looked up and saw me watching.

“Hey, mate,” he shouted from the car.

I was not his mate.

“Paul!” he shouted again. “Let’s go.”

I waited for a van to go past and then I crossed the street to the car.

“What are you doing here?” I asked.

“Get in and I’ll tell you.”

He turned the key in the ignition as I slammed the door shut.

“So you wanna know the news?” he said. His teeth were aimed straight at me.

I shrugged.

“Sure you do, Paul. You can’t help yourself.”

I looked away across the street. A guy from school was riding his moped along the pavement through the crowds. A girl sat behind him; she threw back her head and laughed as he weaved in and out of the scared-looking kids. Her long hair flew about her face so that all I could see was her open mouth.

“I’m a dad, Paul. Can you believe that? I’m a dad and that makes you a big brother. Wait until you see her—she’s too beautiful.”

“Have you got anything to eat?” I said.

“Is that all you can say?”

She’s not my sister, I wanted to say, but it was too late for that.

He swerved out onto the road. There was the sound of brakes and a car hooted behind us.

I saw him check himself out in the rearview mirror.

“Where are we going?” I said.

“To the hospital.”

“I’m hungry.”

“We’ll pick something up on the way.”

We passed the queue outside the bakery, kids, nannies, babysitters from Estonia, older kids from school all lined up. That’s where I go for sandwiches at lunch if I’m not having noodles from the noodle bar. I like watching the blue flames leap up around the noodle pan and I like the sweet peanut sauce. If we have time, Pierre and I cross the Jardin du Luxembourg to go to McDo’s on the boulevard Saint-Michel. We take the boxes back into the jardin and we sit on the metal chairs and watch the couples kissing wetly under the trees as we suck the red sauce off our chicken nuggets.

Maman doesn’t let Cindy buy our bread here; she says it is not artisan. She makes Cindy buy the bread at Kayser, where the baguette has seeds all over that get stuck in my braces and Maman says it is good for me. But I like the bread here. I like bread with white flesh that I can roll into moist balls between my fingers and a crust that breaks into tiny shards that prick my skin.

I like their pépites de chocolat too, if I get to the bakery in the afternoon at 3:50—which I can do after math on Tuesdays—then they are just coming out of the oven. They are soft and long and warm. The woman behind the counter wraps them in a small thin sheet of paper that is like tracing paper, white with pale blue lettering. They droop in my hand. The chocolate chips inside are warm and smeary; the dough molds to the roof of my mouth, and the chocolate turns to liquid under my tongue.

I wished it were Cindy picking me up. When Cindy comes, she takes me

to the bakery and she buys me two pépites de chocolat and a bag of cat’s tongues, flat, green acidy bands covered in granules of hard white sugar that scrape the tip of my tongue. She buys them with her own money so that Maman won’t find out because Maman doesn’t want me eating that stuff.

But Cindy was probably at home, standing in the shower with her flip-flops on, spraying down the surfaces and the floor with Mr. Clean, picking at the dirt between the tiles with a kitchen knife. And Gabriel had come instead.

He had one hand on the steering wheel and with the other he reached into his leather jacket and pulled out a cigar. He lit it at the traffic lights by the Hôtel Lutetia. He sucked at it so that it burned red. “Too bad you don’t smoke,” he said, looking across at me. He had the seat heating on and it was like a furnace beneath me.

“Can’t you turn the heating off?” I asked.

“Don’t you like a hot ass, Paul?” He smiled at me and revved the engine so that the woman in the car next to us turned and stared. I remembered his hand on my mother’s ass, stroking her butt as she lay out beside the pool in Saint-Tropez. She was bursting out of her bikini with her breasts heavy from pregnancy and his hand on her ass, and she never told him to stop. He looked back at the road. “One day you will,” he said and he laughed out loud.

We were on the boulevard Raspail, near where my dad lives. I sent a text to my dad. On my way to the hospital, I wrote, to see the baby. He must have seen the text. He spends his life on the phone—client watching, e-mails, calls. But he didn’t reply.

“Kind of typical that your mother chooses the most expensive hospital in Paris to have her baby,” Gabriel said; his beard was flecked with gold and he was still tanned from the summer. He had a strand of dark tobacco caught on the unshaven hair above the pink of his upper lip.

“You gotta love that,” he said.

“Neuilly isn’t Paris,” I said and I turned away to look at the buildings as we drove west along the quai past the Musée d’Orsay and Les Invalides. We went there in my last year of elementary school. We saw Napoléon’s horse. It doesn’t look like a horse; it looks like a greyhound. It is fine-boned with a coat of thin beige suede. They’ve stuffed it and put it in a glass case. I don’t know how it carried Napoléon. I don’t know how it didn’t just split right down the middle when he got on it to cross the Alps.

The Seine ran beside us, silvery and magnetic in the late-afternoon sun. A barge went by, sliding low through the water, loaded up with black gravel, getting out of Paris. FREEDOM it said on the side of the barge. There was a white Renault Mégane parked up on deck. It must be nice to go somewhere, to escape.

The funny thing is, I used to want a baby brother, I wanted one so bad, but she always said she didn’t want another baby.

“It’s you my baby,” Maman used to say when I was six, when all the other kids’ mothers were having them. She kept her pills in her handbag, a foil packet with pills going round the outside and the days of the week abbreviated on the back in a loop. I used to hope that she would forget her pill, that she would leave the peach-colored pill in the Sunday socket and that by Monday a baby would be growing, hanging from inside her, like a grape.

And then she went and got pregnant when I was in middle school, when everyone else’s mother had stopped doing that. And she did it with Gabriel. She said she didn’t know how it happened. I heard her telling Estelle it would be madness to keep it, that Gabriel was four years younger than her, that she hardly knew him, they’d been together only four months. She said he had no money, that he lived in the back end of the 10ème arrondissement and he played guitar in some unknown band.

“He says it’s just a question of time before they make it big,” she told Estelle. “But, I mean, if he’s undiscovered at age thirty-five, it’s not happening.”

She was in the living room on the telephone when she said that, standing in front of the mirror that hangs above the fireplace, turning to watch the shape her body made. “But at the same time, it could be cute, you know?” She stroked her taut stomach. “Having a baby. This could be my last chance. And what if it’s a girl? I’ve always wanted a little girl.”

The car jerked to a stop at the lights. I looked across at Gabriel and he must have thought I wanted to speak to him because he started talking again.

“You know, Paul, I didn’t think it would be like this. It’s big, you know, a big feeling.” He laughed, a strange, anxious laugh. “And I wonder if I can do it. I mean, am I up to being a dad? I’ve never done it before.” His phone rang. “I cried when the doctor pulled her out. Can you believe that, Paul?”

He answered the phone and his voice changed to his French-lover voice, like he was in a film.

“Yes, my love, how is that beautiful little girl of mine? Tell her Daddy is on his way.” My mother said something and when he spoke again it was in his normal voice. “Yeah, yeah, don’t stress, babe, we are on our way. I’ve got the bag. I’ve got everything. Paul? Yeah, I’ve got him. We’re on the Champs, we’ll be there in ten minutes.”

Gabriel took a right turn off the Champs-Élysées, dipping down into the underpass. The last time I was in this tunnel, I was with my parents and we were on our way to my grandparents for lunch. My dad was driving. We were late and my parents were arguing. I was in the back gaming, trying to block them out. The smell of Maman’s scent lay heavy on the leather seats. She was putting on her lip gloss, making her mouth sticky and round.

“Have you got the macaroons, Séverine?” my dad had asked.

“No,” Maman said. She’d pressed her lips together and smiled at herself in the mirror.

“Where are they?” he said.

She snapped the sunshade back up. “No idea.”

He held the steering wheel tight.

“You do this on purpose, you do it to piss me off, to upset my mother, I know you do.”

“You’re right,” she said, turning to stare at him. “I do.”

“You’re a bitch, Séverine,” he said.

“Perhaps.” I saw her shrug her shoulders as she said that. She turned away and looked through the window at the gray tunnel wall. “But it’s you that made me that way.”

It used to be hot, molten anger between them that ended in kissing, their bodies thrust up against each other. I was used to that. But this was a new anger; it was brittle and rigid, made of iron like the railings that go all the way around the jardin, high black railings dipped in gold and shaped like spears that you cannot climb over.

The hospital was lit up yellow against the dark pine trees of Neuilly. There was a silver and glass entrance with a big revolving door. The people coming out looked like they’d just gotten off a flight from Dubai. Inside there was a bank of receptionists speaking English into telephone headsets. There was a pink marble floor and a café with potted palms. It looked more like a hotel than a hospital, only the guys sitting in the café had see-through dying skin and tubes coming out of their noses.

Maman was alone when we walked into her room. She was up high on a metal bed, talking on her phone. There was no sign of the baby. I wondered if she had given it away, the way she gives away her clothes when she doesn’t want them anymore.

“I know that, Maman. I’ve told them already; they are taking her to the nursery tonight.” Her voice was tight. “Listen, I’ve got to go, Gabriel and Paul are here. Come tomorrow, not too early. I’ve got the consultant coming first thing.”

She put the phone down beside her bed, looked up at me, and smiled; it was her big white smile. She was barefoot and stretched out with her dark hair spread against the pillow. Her nails were painted red; her black sunglasses were pushed to the top of her head. She looked like she was hanging out in a hotel room somewhere, taking a rest before she went down to the pool. She wore a little gray top with thin straps, so her tanned shoulders were almost bare. The curve of her breasts showed, and her stomach was flat so that I wondered if there’d ever been a baby in there at all.

Even in the ho

spital, the magic was there. The air lay still against her skin and it was as if her every curve, every contour, every bone was made to be seen. She knows it’s happening, that you are watching her. She’s at ease with the deal—she’s the one who is and you are the one who admires. That is the way it has always been. I’ve seen photos of her when she was sixteen, in blue denim, breaking boys’ hearts. Sometimes I wonder if Maman exists when there isn’t someone there to look at her.

“My love,” she said, holding her arms out to me.

I took a step toward her, but Gabriel got there first. He kissed her on the mouth.

“How’s that beautiful little girl of mine?” he said.

I waited until he backed away. I stepped forward and bent my head. Her lips were soft and cold against my forehead.

“My little Paul,” she said. I closed my eyes and breathed in the scalp beneath her hair. She smelled of jasmine. I put my arms around her neck, my hands underneath her hair, holding her to me until I felt her stiffen and she pulled away.

“We got stuck in the tunnel,” I said. “I got claustrophobia. It was dark in the tunnel and there was all this red light from the brakes ahead, and the speedometer dial on the car was glowing green in my eyes and everything was pushing down on me; I was suffocating and there were exhaust fumes and Gabriel was smoking a cigar so I couldn’t breathe.”

“My poor baby,” she said, but she wasn’t looking at me, she was searching through the bag that Gabriel had brought with him. “Did you remember the cream, babe?” she said.

“Yeah, I remembered the cream.”

Someone had given her a big bouquet of pink roses. Pink like lingerie. They sat in a vase next to the television. There must have been thirty roses in that vase, tightly packed, with masses of folded petals. The stems were strapped together with strands of raffia so they couldn’t move; they made me think of the tunnel, of being trapped.

“Hey, Paul,” Gabriel said. “Come and meet your sister.” He walked over to a small room that was connected to my mother’s room by a glass wall with a door. He pushed open the door and switched on the light.

I Love You Too Much

I Love You Too Much